The exhibitions "Textual arts" (Leipzig) and "Impressions premières" (Lyon) offer insights into the early history of European printing. The exhibitions place these early printed books in front of the increasingly nervous attentiveness of our digital age, and in such a way as to make evident its aesthetics as well as its functionality.

The libraries of the University of Leipzig and of the City of Lyon each hold important European collections, especially early printed books. Over the centuries each has developed its own policy of collecting, and yet their holdings duplicate as well as complement each other and thereby together provide a representative range of phenomena that makes us aware of all that was at stake in creating a single page.

In the period from 30th of September 2016 to 29th of January 2017 the two parallel curated exhibitions with the topics "Textual arts" (Leipzig) and "Impressions premières" (Lyon) offered insights into the early history of European printing. The exhibitions placed these early printed books in front of the increasingly nervous attentiveness of our digital age, and in such a way as to make evident its aesthetics as well as its functionality.

The libraries of the University of Leipzig and of the City of Lyon each hold important European collections, especially early printed books. Over the centuries each has developed its own policy of collecting, and yet their holdings duplicate as well as complement each other and thereby together provide a representative range of phenomena that makes us aware of all that was at stake in creating a single page.

These two exhibitions jointly presented, and in conjunction with one another, books from a German and a French library. The catalog unites the exhibitions from Leipzig and Lyon and contains identical contents in French and German.

Looking backwards from the digital age

On the screens of our laptops and tablets we experience myriad ways of connecting text and image, moving top to bottom or left to right. Aesthetically it is like dealing with scrolls, the form of storing and conveying information before the codex, and the bound book. Turning the pages is now replaced by commands which allow for consecutive reading or browsing, even jumping. New hardware will undoubtedly bring new ways of orienting the reading process, new software will open up new ways of representing text.

Typical for digital text formats are hyperlinks or connections which open new windows of text or imagery on the same screen. Texts are laid one over another or placed in front of one another. On screen, we do not only navigate from one text passage to the next, we also jump to other texts elsewhere. Thus digital text design erases the formats we have become used to in the world of printed books.

However, the printed page is not going away easily, since it defines the reading culture through regimes of legitimacy and its own politics of truth. Most importantly, the page coordinates literature (in the widest possible sense of the word) and has become an established agent of significance and meaning.

The word 'reading' itself makes it abundantly clear to what degree text formatting has become indispensable and also profitable for us. Almost everything can be 'read', which gives us enough reason to have a closer look at what is typical reading, i. e. the reading of texts. This exhibition project begins with the assumption that text formatting always had an impact on reading and therefor was done with respect to it. We see from the early attempts that it was quite difficult to turn texts into readable formats.

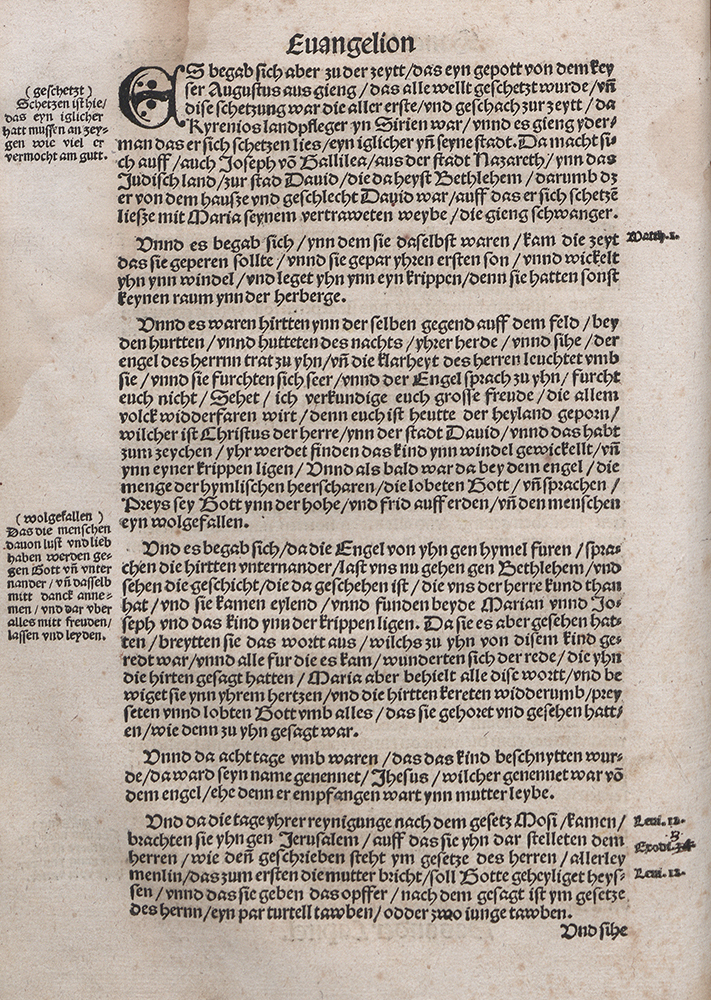

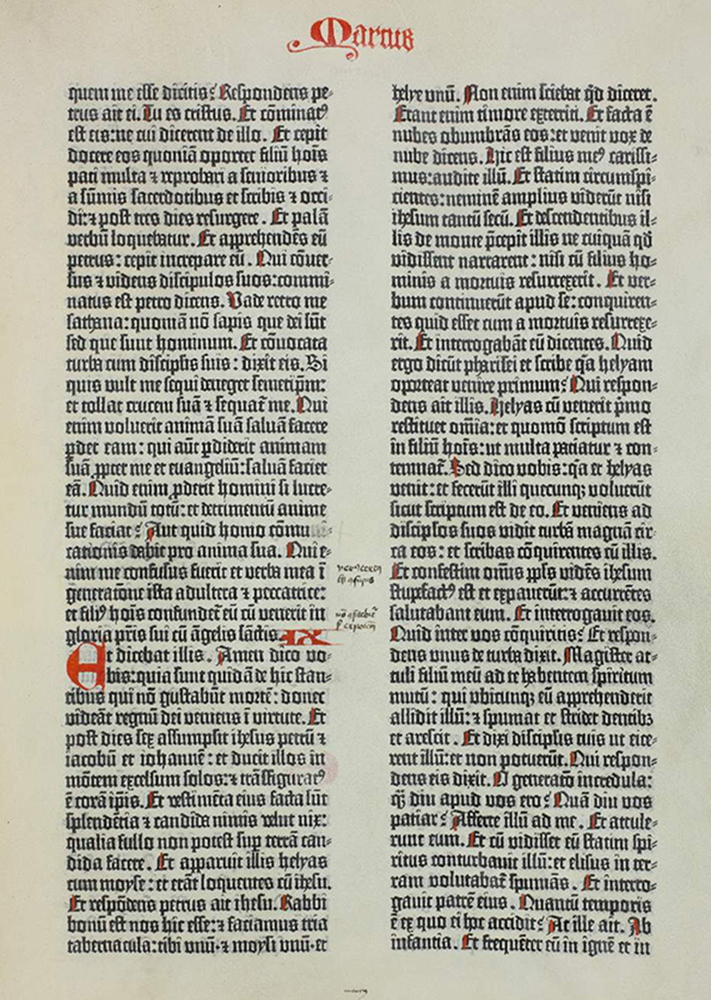

The era 1455–1535

There is no sudden appearance of print. The rules observed by most printers really developed over at least the first 70 years after the European invention of printing with moveable types. Many books clearly show signs of experimentation, not all of them successful to our eyes. To achieve readability was certainly the aim of the printers. The very fact that the page number was only printed in the 16th century indicates that formatting a printed page was for a long time no sure thing. The idea of 'the page' with its own identity grew slowly – which may indeed explain why it vanishes no less slowly today.

What we here call 'the invention of the printed page' is effectively a bundle of procedures which were altogether newly oriented when printed texts were first produced for a wider public. Between 1455 (when Gutenberg produced the first results with moveable type), and 1535 (when books by Luther were circulating all over Europe) we discern in hindsight an epoch in which it took some time, and no small amount of hard work, to create the printed page.

Looking backwards from the digital age

On the screens of our laptops and tablets we experience myriad ways of connecting text and image, moving top to bottom or left to right. Aesthetically it is like dealing with scrolls, the form of storing and conveying information before the codex, and the bound book. Turning the pages is now replaced by commands which allow for consecutive reading or browsing, even jumping. New hardware will undoubtedly bring new ways of orienting the reading process, new software will open up new ways of representing text.

Typical for digital text formats are hyperlinks or connections which open new windows of text or imagery on the same screen. Texts are laid one over another or placed in front of one another. On screen, we do not only navigate from one text passage to the next, we also jump to other texts elsewhere. Thus digital text design erases the formats we have become used to in the world of printed books.

However, the printed page is not going away easily, since it defines the reading culture through regimes of legitimacy and its own politics of truth. Most importantly, the page coordinates literature (in the widest possible sense of the word) and has become an established agent of significance and meaning.

The word 'reading' itself makes it abundantly clear to what degree text formatting has become indispensable and also profitable for us. Almost everything can be 'read', which gives us enough reason to have a closer look at what is typical reading, i. e. the reading of texts. This exhibition project begins with the assumption that text formatting always had an impact on reading and therefor was done with respect to it. We see from the early attempts that it was quite difficult to turn texts into readable formats.

The era 1455–1535

There is no sudden appearance of print. The rules observed by most printers really developed over at least the first 70 years after the European invention of printing with moveable types. Many books clearly show signs of experimentation, not all of them successful to our eyes. To achieve readability was certainly the aim of the printers. The very fact that the page number was only printed in the 16th century indicates that formatting a printed page was for a long time no sure thing. The idea of 'the page' with its own identity grew slowly – which may indeed explain why it vanishes no less slowly today.

What we here call 'the invention of the printed page' is effectively a bundle of procedures which were altogether newly oriented when printed texts were first produced for a wider public. Between 1455 (when Gutenberg produced the first results with moveable type), and 1535 (when books by Luther were circulating all over Europe) we discern in hindsight an epoch in which it took some time, and no small amount of hard work, to create the printed page.